Seeking Submissions

January 3, 2022

CoJDS’ Curriculum Development–A Closer Look

January 17, 2022by Rabbi Dr. Uriel Lubetski and Mrs. Rivky Krestt

If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

Lewis Carrol

In teaching any subject, it is important for instructors to clarify their goals so that they choose the correct path to accomplish their objectives. We set out to develop mishna curricular materials that are structured, challenging, and current. The materials can be used as preparation for studying gemara or stand alone as an entry into the library of Jewish literature.

How do you design rigorous, stimulating, and relevant curricular materials that facilitate deep mishna analysis, provide students with an understanding of the world of chazal, and deliver insights into the development of halacha? First, Mishna Standards need to be identified to clarify and unpack these objectives. Then, Enduring Understandings are determined to provide instructors with the key ideas critical for students to retain. Finally, Essential Questions are pinpointed to drive the lesson and motivate the students to analyze the material and construct meaning.

In other words, we used the Understanding by Design (UBD) model, which utilizes backward design, the practice of looking at the outcomes in order to design curriculum units, performance assessments, and classroom instruction.

Our mishna standards were adapted from the Israeli Ministry of Education standards. Since our program is for English speakers, we convened several educators from around the United States to discuss the standards and updated them to reflect the needs of the English-speaking public.

They comprise six categories:

- Mishna Fundamentals

- Halachic Concepts

- Vocabulary and Reading

- Structure and Terminology

- Comprehension and Application

- Relevance and Values

We then derived the Enduring Understandings and Essential Questions from the mishna standards.

To demonstrate these ideas, let’s use the Halachic Concepts standard as an example and apply it to a real mishna, Bava Kamma 3:1.

הַמַּנִּיחַ אֶת הַכַּד בִּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים וּבָא אַחֵר וְנִתְקַל בָּהּ וּשְׁבָרָהּ, פָּטוּר

Standard: “To define the concepts and explain their significance.” When studying this mishna, this standard can be more specific: “To define the concept of בור and explain its significance.”

Enduring Understanding: “Readers can understand the background of a topic and uncover the author’s overall meaning by defining concepts.” This understanding clarifies the “why” of studying and defining concepts. Students perceive that identifying the concept in this passage and then defining it provides them with the information to understand the case properly. This understanding is enduring in that it is something that students should retain and applies to many other mishnayot.

Essential Question: “How can identifying, classifying, and defining concepts help with an overall understanding of a mishnaic passage?” This can be applied specifically to the concept of ruc and how defining it helps with understanding the law in this mishna. This question provokes discussion and motivates students to engage with the material. Furthermore, it can serve as a summary question after students finish learning a topic. It ensures that the specifics that were studied in class relate to a broader theme which aids in retention of material.

When preparing a lesson, a teacher can review all the standards, understandings, and questions and see which apply to the mishna and then develop and design their lesson. This requires a lot of work and effort. As an alternative, we developed a framework created and ready to use for each mishna unit in the Sulamot LaMishna curriculum to ensure that the standards, understandings, and questions are constantly utilized to create rigorous and engaging lessons. This structure makes the material easier to access and understand for the student and assists in developing mishna skills.

Each unit in the curriculum has the following sections:

- מִשְׁנָה וּמִילִּים – Mishna and Vocabulary: We start with the mishna and translation of difficult words and phrases. Students will develop the vocabulary and reading skills necessary to read mishnaic passages accurately. These skills include translation, pronunciation, and inflection. Furthermore, parts of the mishna are suggested to be learned by heart.

- שְׁאֵלוֹת מַנְחוֹת – Guiding Questions: These questions are the main issues (general life issues and specific mishna issues) that will be discussed in the upcoming unit. They serve as excellent discussion starters.

- תּוֹרַת חַיִּים – Relevance and Values: The mishna can give us insight into the world around us. This section introduces a real-world issue that the mishna can help us understand. Students will identify one of the values stemming from the mishna, internalize it, and apply it to their lives.

- יְסוֹדוֹת תּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל־פֶּה – Mishna Fundamentals: This includes basic knowledge about the nature and characteristics of the mishna, its transmission from generation to generation, information about major tannaim, and navigation through the mishna.

- מִבְנֶה וּמוּנָחִים – Structure and Mishnaic Terminology: Students will attempt to recognize, divide, classify, and connect the structural components of the mishna utilizing the כאמד”ט method (Title – כּוֹתֶרֶת, Speaker –אוֹמֵר, Case – מִקְרֶה, Law – דין, and Reason – טַעַם – see later for more on this.) Students accomplish this by recognizing specific mishnaic terms.

- מוּשָּׂגִים – Halachic Concepts: To fully grasp the mishna, students must delve into the underlying concepts of the case or disagreement at hand. Explanations of concepts will be found here.

- הֲבָנָה וּפַרְשָׁנוּת – Understanding and Interpretation: This includes a more in-depth study of the mishna’s details and its context. This component is designed to help students understand the rulings of the mishna and to apply what they learned to new problems. Building these thinking skills will ultimately sharpen their minds and make mishna learning more stimulating.

- סִיכּוּם – Summary: After learning the mishna, there will be a summary task such as completing a chart, answering questions, or sketching a drawing.

We start with the mishna text and translation of difficult words and phrases, followed by reciting the mishna aloud. Then, we present the goals of the unit through guided questions. They can serve as excellent discussion starters and can be used throughout the unit before and after students have studied the sources. The relevance and values section piques student interest and demonstrates how the mishna can be relevant to their lives. Mishna fundamentals, mishnaic terminology and structure, and halachic concepts present important background information, building blocks, in order to understand the mishna. Following these introductory sections, all the obstacles to understanding the mishna are cleared. Students can now study the mishna in-depth clarifying the halachot and their reasonings. We close the unit with a summary task to emphasize the main points and then apply the mishna to students’ lives.

The material included in Sulamot LaMishna gives the teacher freedom to use their energies to focus on designing a stimulating lesson plan. Each unit has suggestions for lesson plans, activities, and ways to personalize and internalize the material. We trust that teachers will benefit from the articulation of this model and employ it in developing their lessons.

A student who knows how to learn and is actively engaged in meaning-making will love to learn. Therefore, in our curriculum, much emphasis is given to:

- Structure and Terminology – decoding the mishna using the כאמד”ט system to identify the structure of a mishna, and

- Relevance and Values – applying the principles and ideas of the mishna to the lives of the students.

In doing so, students will be excited to ask questions, curious to learn the reasons behind the halacha, and motivated to understand each part of the mishna. Let us explain these two sections a bit more.

כאמד”ט

Although mishna has its own language, methodology, and mission, mishna is most often studied as an entry point to studying gemara and sometimes the mishna is not analyzed fully. כאמד”ט is a methodology that allows teachers to guide the students into an enquiry of mishna as a work on its own that will later serve as a stepping stone for Talmud.

The כאמד”ט method develops student skill in analyzing the structure of the mishna which prepares them to understand the information in the mishna. The כאמד”ט method is founded on the principle that most mishnayot potentially have five components.

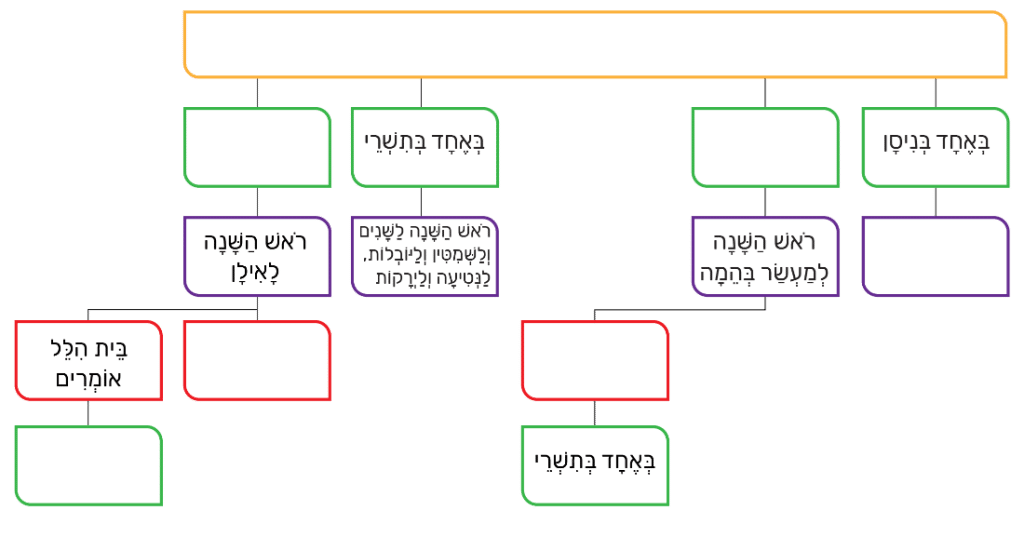

· כּוֹתֶרֶת (orange) – title of a mishna

· אוֹמֵר (red) – speaker listed in the mishna

· מִקְרֶה (purple) – case presented in the mishna

· דין (green) – mishnah’s ruling on the case presented

· טַעַם (light blue) – reason behind the ruling of the mishna

Once students can identify the components, they have the tools to unpack and understand the mishna completely, including who is speaking, what the issues are, and what the halacha is. With this knowledge, the students can understand the ancient discourse and are primed to deciphering the issues that will be discussed in the Talmud and the halachic texts that ensued from there.

Let’s look at a כאמד”ט example. The first mishna in Rosh Hashana fits nicely into a כאמד”ט table. It has four out of the five elements present. The mishna reads:

אַרְבָּעָה רָאשֵׁי שָׁנִים הֵם. בְּאֶחָד בְּנִיסָן רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה לַמְּלָכִים וְלָרְגָלִים. בְּאֶחָד בֶּאֱלוּל רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה לְמַעְשַׂר בְּהֵמָה. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמְרִים, בְּאֶחָד בְּתִשְׁרֵי. בְּאֶחָד בְּתִשְׁרֵי רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה לַשָּׁנִים וְלַשְּׁמִטִּין וְלַיּוֹבְלוֹת, לַנְּטִיעָה וְלַיְרָקוֹת. בְּאֶחָד בִּשְׁבָט, רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה לָאִילָן, כְּדִבְרֵי בֵית שַׁמַּאי. בֵּית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים, בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר בּוֹ:

Figure 1 is the table that students are asked to complete. The color coding and clearly delineated boxes make it easy for the students to figure out.

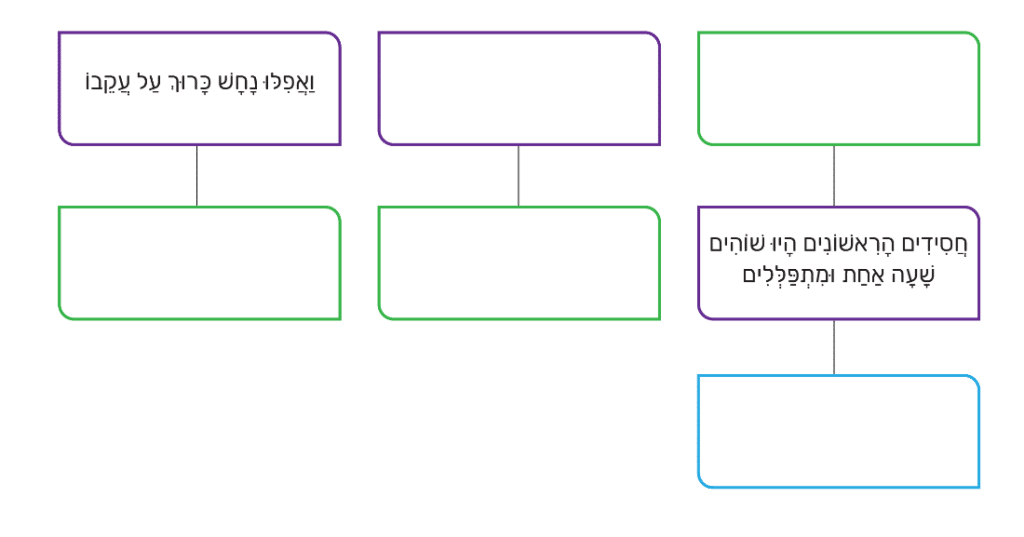

To get the idea, let us look at another mishna from Brachot that has a different structure and includes a ogy – a reason. The mishna in Brachot 5:1 says:

אֵין עוֹמְדִין לְהִתְפַּלֵּל אֶלָּא מִתּוֹךְ כֹּבֶד רֹאשׁ. חֲסִידִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים הָיוּ שׁוֹהִים שָׁעָה אַחַת וּמִתְפַּלְּלִים, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּכַוְּנוּ אֶת לִבָּם לַמָּקוֹם. אֲפִלּוּ הַמֶּלֶךְ שׁוֹאֵל בִּשְׁלוֹמוֹ, לֹא יְשִׁיבֶנּוּ. וַאֲפִלּוּ נָחָשׁ כָּרוּךְ עַל עֲקֵבוֹ, לֹא יַפְסִיק:

The structure of the mishna presented visually (Figure 2) makes it easy to engage the students in a discussion of the reason for the rulings. What is the importance of כוונה? How does one garner the proper intent for prayer and under what circumstances can one interrupt oneself? Brainstorming with students to think of the most extenuating circumstance can be an engaging exercise to emphasize the importance of כוונה.

To be fair, very few mishnayot have all five elements of כאמד”ט present. It is much more likely to find a mishna that has three or four elements. Still, taking all the mishnayot together, the students can utilize their analytical skills to decode the mishna and break it down to its composite parts, ultimately arriving at a better understanding of the mishna.

Relevance and Values

The ‘Relevance and Values’ section assumes that students must be engaged in their learning and see the relevance of the material being studied for the teacher to be successful in instilling the mishna’s ideas and concepts. It can be a hard task to relate the mishna to modern day life. The Sulamot approach distills the values and principles from the mishna and then applies these ideas and concepts to the everyday life of a student. This accomplishes two important goals. It engenders relevance and motivates the student to learn the mishna. In the mishna unit, we include a ‘Relevance and Values’ section in the beginning to pique student interest, and at the end of the unit to apply the values and principles of the mishna to the student’s life.

Let’s see an example: The mishna in Brachot 1:2 discusses the time for shacharit. Specific times for mitzvot can be hard for people to understand. These questions are not novel, nor unique, but they need to be addressed. The ‘Relevance and Values’ section begins with a video about a person’s morning routine and how important it is for his day. It drives home the point that certain activities must be done each morning before going off to start one’s day. The ‘Relevance and Values’ section concludes with a conversation between fictional characters discussing the importance of time in our lives:

Yaakov: After learning about the times for קְרִיאַת שְׁמַע, I realized that so many mitzvot have to be done at an exact time.

Rivka: What do you mean?

Yaakov: Well, it would be inappropriate to blow the shofar in the middle of the winter or eat matzah in the fall.

Sometimes, the connection to everyday life is less didactic. The unit on Brachot (4:5) opens with a fictional conversation that discusses what happens when one does not have time to complete all of tefilla:

Rivka: [as she gets on the bus] Oh no! I haven’t said my morning tefillot yet. What am I going to do? We are leaving on a trip today and my counselor was clear that we had to come to camp ready to go and I totally forgot to pray at home. Can I pray on the bus?

Grandpa Dave: You can! Let’s see the mishna for details.

The ‘Relevance and Values’ section is a good trigger for discussing the larger issues and for students to internalize the lessons of the mishna – both practical and philosophical.

Assessments

We have discussed standards, understandings, and essential questions and demonstrated how we can use them in classroom instruction. What’s left are assessments, both informal and formal, of which the building blocks are embedded in each unit. Discussions triggered in the ‘Relevance and Values’ section can easily be turned into exit tickets or journal entries that can be collected. The drills connected to כאמד”ט are easily turned into manipulatives, worksheets, or graded quizzes. Since every unit is organized and begins with a clear idea of what students should know, the challenge of having a sense of how we want our students to demonstrate that knowledge is mitigated. The beauty of having a curriculum mapped out means that assessments can be planned and implemented in a consistent and structured way and that teachers can use their energies to tailor their assessments to the student sitting in front of them. Assessments are not one size fits all; they can (and should) be personal and adapted to specific classrooms.

The mishna curriculum we’ve created uses standards identified to ensure that all students will know certain terms, personalities, and key ideas. The material is engaging and visually stimulating and, if a school is interested, can be used on our digital platform. It is Sulamot’s hope that our curriculum is a stepping stone for students in their journey of Torah learning.

Rabbi Dr. Uriel Lubetski was a teacher and administrator for 24 years in New York, Memphis, and Baltimore. Since he made aliya, he is the Director of Education, English Division, at Sulamot, where he writes Judaic studies curriculum for English speaking schools. He wrote his doctorate on applying the principles of Project Based Learning to a Tanach lesson. He welcomes any thoughts or comments to [email protected].

Rivky Krestt is a seasoned Jewish educator. Prior to moving to Israel, she held department chair positions in Jewish studies at day schools and community schools in the United States. In addition to being a classroom teacher, she teaches online and writes curriculum. Rivky holds a master’s degree in Curriculum Theory and Development from The University of Maryland. She lives in Efrat, Israel, with her husband and three children.

Schools that are interested in learning more about Sulamot’s curricular materials are welcome to see print sample, contact the authors, or email [email protected].