Seeking Submissions

January 3, 2022

CoJDS’ Curriculum Development–A Closer Look

January 17, 2022by Mrs. Elana Katz

There are many challenges we face when trying to design a chumash lesson. Most of our students are familiar with the stories and insights that we aim to teach. Some can demonstrate mastery of the story before we have discussed it. Some students are quickly able to understand a Biblical text, while many of their classmates struggle with words and phrases that should already be independently understood. Some students come from homes where Torah study is of paramount importance, while others do not share these specific priorities. These variables present educators with many competing factors to keep in mind. How does one design a lesson that will be new, rigorous, and engaging to students of all levels and backgrounds?

When designing a chumash lesson, regardless of the grade, community or location of the school, my guiding principle has always been to ensure that the lesson will require the students to be ameilim baTorah and truly engage with the text. For the past 15 years, I have taught chumash to different grade levels in different areas of the country. My experience has taught me that there are 3 crucial factors which comprise a successful course. The first and foremost is that the students are actively working with the text of the chumash. The next component is a strong focus on critical thinking skills. Finally, there is constant and consistent skill development and practice. This is practiced daily, but in small increments of no more than 5-7 minutes per lesson. Additionally, the skill building is directly relevant to the lesson and the students understand and appreciate the value of the drill.

Actively Engaging the Text

In order for students to feel the value of learning chumash, they need to feel a sense of self-discovery from the pesukim that are in front of them. When designing a lesson, I aim to structure the lesson with an opening that invites the students to notice the nuances and discrepancies in the text. It is always a priority that they are able read the chumash themselves, regardless of skill level, and begin to notice the questions and issues independently.

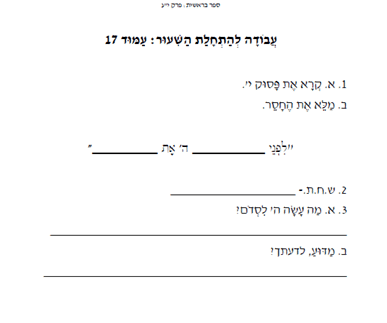

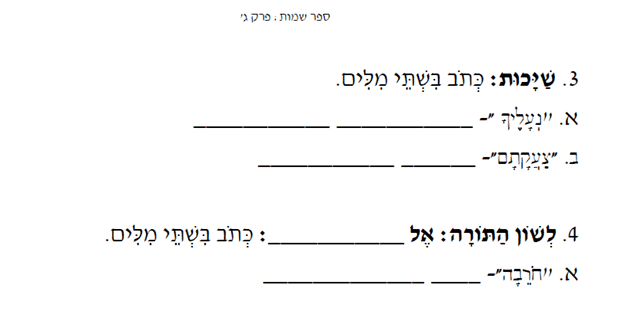

Figure 1 is from a 2nd grade lesson which introduces the story of the destruction of Sodom. At the start of the unit, the students were assigned five shorashim to master. By carefully choosing which five shorashim, the students are given the necessary tools to understand parts of the text independently. This worksheet merely asks the students to fill in the blanks. All students who can read Hebrew are able to correctly copy the words and feel a sense of pride in their ability to work with the text. The students learn that the text is relevant because they feel that they can understand parts of it. This introductory lesson requires the students to copy from the text, use their knowledge of shorashim and then analyze the material. (Some students do receive a copy of the worksheet with an English translation, in order to provide differentiated instruction for all learners.) The students are excited to share their opinion and demonstrate their understanding of the material.

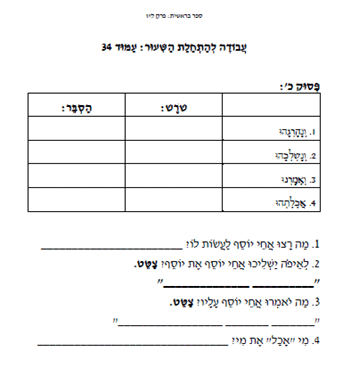

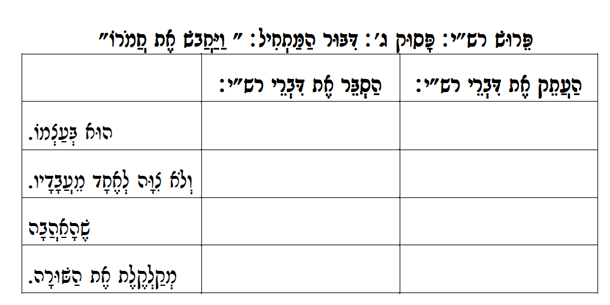

The worksheet shown in Figure 2 is taken from a fourth-grade lesson. It also requires the students to read from the chumash in order to answer the questions. As in second grade, the shorashim have been thoughtfully assigned in order to give the students the necessary skills to work with the text. By asking the students to quote from the text, they are forced to use the text and select the correct words instead of offering answers from memory.

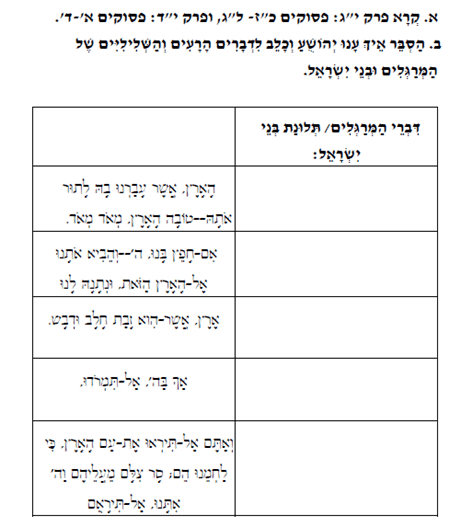

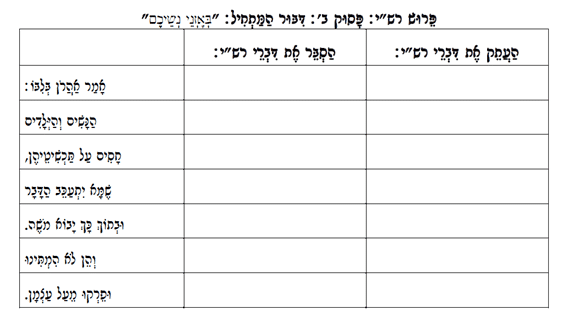

The worksheet in Figure 3 is taken from a 7th grade unit on the meraglim. After the students have learned the reaction of Bnei Yisroel to the negative report of the spies, they are (then) required to use that information while working with a new text. Here, the students are asked to quote the negative words of Bnei Yisroel that prompted Yehoshua and Calev to respond with positive encouragement. Again, the students are required to work with and correctly quote from the text. This challenging approach requires the students to actively engage the text, both by analyzing the words for the correct answer and by quoting. (Again, students who struggle with Hebrew are given a worksheet that has English translations.) When appropriate, I will break off a small group and assist them as they complete assignments of this nature. By doing so, the students who are not proficient at independently working with the text receive the support they need, while proficient students are challenged to actively work with the text.

Critical Thinking Skills

Regardless of the grade level, there are always students who are excited to share that they “already know this story.” It is with pride and excitement that I answer, “Don’t worry – you will still learn something new today.” When designing a lesson, it is important to be focused on being able to present a new angle which they may not have thought of yet. By constantly uncovering new layers of depth in Torah study, the students experience excitement in their Torah learning.

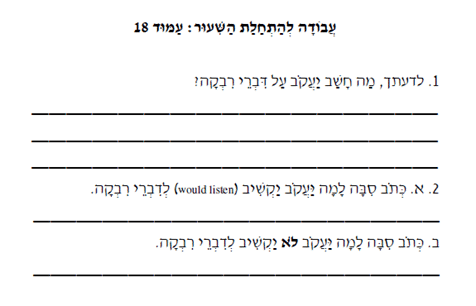

The worksheet shown in Figure 4 is taken from a 3rd grade unit that discusses Yaakov stealing the brachos from Esav. After learning the pesukim that relate Rivka’s command to Yaakov that he trick Yitzchak, but before the students learn Yaakov’s response to her, they are asked to analyze the situation. By asking the students to consider why Yaakov should listen to Rivka as well as why Yaakov should not listen, they are forced to grapple with the conflict Yaakov himself faced and considering opposing viewpoints. When students explore the dilemma in this manner, the conflict comes to life for them.

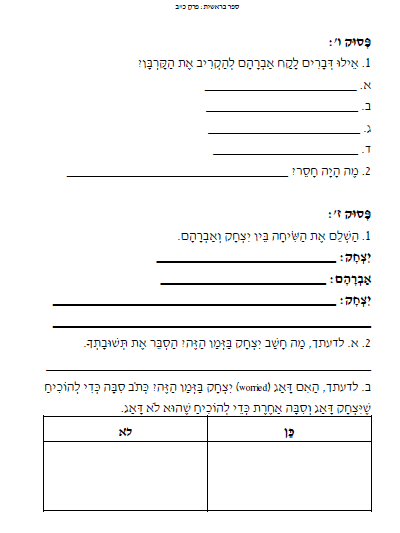

Figure 5 shows a worksheet taken from a 3rd grade unit on akeidas Yitzchak. The students are asked to complete this worksheet after the pesukim have been read and explained in class. By providing the source of each pasuk, the students are able to use the text to find specific answers. Once the pesukim are reviewed, the students are asked to analyze Yitzchak’s perspective by providing proofs for their answers. These answers are not based on their opinions, but on the words of the text or on Rashi’s commentary. Again, they are being asked to look at an issue from various perspectives.

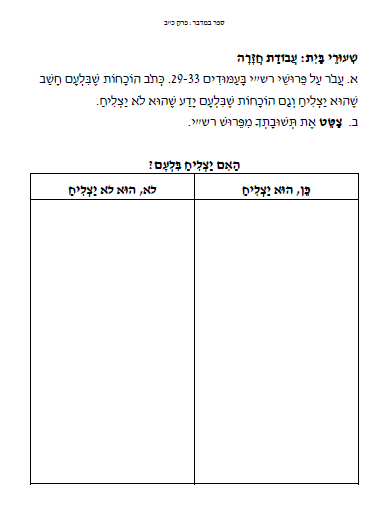

A homework sheet from an 8th grade unit on Parshas Balak is shown in Figure 6. This worksheet was presented to the students at the end of the perek and after much discussion about Bilaam’s ambivalence towards going with Balak to curse Bnei Yisroel. The students are asked to review the notes they took, based on Rashi, to decide if Bilaam believed that he would be successful in cursing Bnei Yisroel. The students are then directed to correctly quote the words from Rashi to support their opinion. This forces the students to analyze the material on a deeper level, and also forces them to analyze Rashi’s words in order to correctly choose the proper quote to support their answer.

Students can also be prompted to explain what they think will happen and why they think so. In this case, students can be asked to explain why they think Bilaam ultimately chose to go with Balak after experiencing doubts. The discussions become more meaningful when students are prompted to share what resonated with them regarding the struggles and conflicts that are presented in the stories. This technique is particularly effective with elementary school students. They are eager to share their perspectives, experiences, and the life lessons that they elicit from the text.

Skill Development and Practice

In order to ensure that students will be able to actively use the text, students must be properly taught how to understand the text. It is important to make sure that students are only working on an appropriate number of skills per school year in order to ensure that they are able to master those skills.

The basic building block of working with the text is shoresh recognition and understanding. Students of all grade levels benefit from being assigned shorashim to learn before each perek. In second grade, my students typically learn five new shorashim per perek, while in middle school, they learn ten shorashim per perek. Additionally, I begin to assign my third-grade students one or two common vocabulary words per perek that will reappear throughout their years of Torah study. (Students who struggle to master all the assigned shorashim for each perek receive a modified amount in order to ensure that they are building their repertoire of shorashim. The modified shorashim are specifically chosen based on the frequency in which they appear in the perek.)

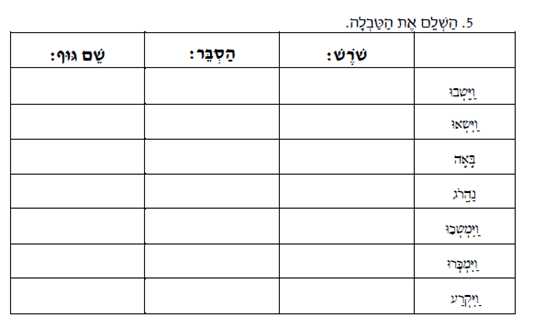

At the start of many lessons, the students are asked to complete a shorashim chart. These charts break down Biblical Hebrew into the shoresh, translation and pronoun. By beginning the lesson with breaking down these words, the students already know what to expect and can independently understand many phrases from the pesukim in that day’s lesson. They express excitement and motivation that they have now been given a tool which helps them understand the text with less assistance.

By completing a shorashim chart (Figure 7) with my students before we learned the pesukim about mechiras Yosef, the students were given the framework needed to anticipate and understand the text.

Another important chumash skill is the ability to break down complex words. As always, it is most meaningful when skills work is done in context. On nightly homework sheets, students receive 2-3 examples of words to break down, regardless of the grade level. The constant and consistent reviews reinforce these skills and helps the students retain them on all grade levels.

The questions shown in Figure 8 are taken from a fifth-grade homework packet. These examples are reviewed briefly in class the next day, providing a way to consistently review skills without making the lesson feel too technical.

Another important skill that students benefit from consistent exposure to is mastery of Rashi script. Once the students have learned Rashi script, they are provided with Rashi charts to complete each time a peirush is covered in class. Figure 9 is taken from a 3rd grade worksheet on akeidas Yitzchak, and Figure 10 is taken from a 6th grade worksheet on cheit ha’eigel.

Regardless of the grade level, these Rashi charts provide many benefits. Many students, even at the middle school level, struggle with mastery of all Rashi letters, particularly lamed and tzadi. By copying the words of Rashi, students get the necessary practice and review of the letters. Additionally, it ensures that all students have read through the entire commentary of Rashi at least once.

These charts also provide the opportunity to differentiate instruction. When the commentary is broken up clause by clause, stronger students will often understand the main idea of the commentary simply by copying it. They feel challenged, and when successful, feel a sense of pride and accomplishment. The students who struggle with language appreciate that it is explained clause by clause in class and feel supported to fully understand the commentary. Once we have ensured that the students have the resources needed to analyze Rashi or quote an answer from Rashi, we are able to give more rigorous assignments. By utilizing all the techniques mentioned, students are given the necessary tools to become successful chumash learners. These methods provide a framework for students to be actively engaged in the learning process. They are able to discover the hidden and glaring issues in the text and, in my experience, are able to become ameilim baTorah.

Mrs. Elana Katz is a Tanach teacher, with specific passion for creating curriculum and teaching Chumash. She has taught Tanach to grades 2-12 for the past 15 years and currently teaches Chumash to the lower and middle schools at the Fuchs Mizrachi School in Cleveland, OH. Contact Mrs. Katz at [email protected].