The ADHD Whole-Class Approach

July 18, 2022

Apple and the Tree – Why Helping the Parents is the First Step to Helping the Children

July 18, 2022by Miriam Gewirtz

The fidgety and hyperactive child has always been around. The inattentive or impulsive student has always existed. We all know that in the days that our grandparents grew up and especially our great grandparents grew up the common expression was that “children should be seen and not heard.” When kids misbehaved or did not fit into the societal mold, they were considered “bad”, and they were often ridiculed and punished in order to be “taught” right from wrong.

Formerly called hyperkinesis, ADHD began to be better understood through the research of Virginia Douglas in the 1970s. Particularly important was her work showing that the behavior of children with hyperkinesis seemed to be rooted in the inability to sustain focus or control impulses, which led to the new name of attention deficit disorder (ADD.) Due to her research and the work of others, the world began to understand that this disorder is rooted in biology (there is even a genetic component) and not in poor parenting or poor self-discipline. According to contemporary naming conventions, the disorder called ADHD includes both the inattentive (or distractable) type and the hyperactive type.

When observing the deficits in children with ADHD back in the 1800’s (it didn’t have a name yet,) people assumed a moral diagnosis. The assumption was that these children chose not to obey or pay attention out of laziness or spite; they needed to try harder to succeed. In those days they utilized reform schools and even institutionalized children who were not able to conform. Now that the mindset has changed, ADHD is accepted as a medical diagnosis, recognizing that the symptoms have an underlying neurological cause and don’t reflect a moral failing. The evolution of this model has helped to combat stigma and prejudice by explaining the reasons behind the behaviors. Yet even with all this progress, when we tell a parent that their child has a disease of the mind, they most likely feel shame, fear, or a sense of failure. The children, too, can take the diagnosis of ADHD as a negative – a handicap that they will be saddled with for the rest of their lives.

The Disability Model

We are used to using a disability-focused model where we identify areas of weakness in children. When we look at a child with ADHD, we tend to describe him as unfocused, scattered, disorganized, head’s in the clouds, all over the place, jumping off the walls, etc. Would it also be accurate to describe these students with any of the following character traits: spunk, persistence, charm, creativity, or hidden intellectual talent? I have yet to attend a problem-solving meeting in a school where these descriptions are the main ones used.

The reason for this is because students with ADHD are living in a very challenging world. Imagine a bright first grade student who struggles with sustaining attention. He is placed in the lowest reading group because he can’t maintain his focus while reading a sentence. He is always the last to shout out an answer during math drills. The process of writing is so hard for him. Even if his teachers never criticize his performance, he will feel like he is failing because he is just not measuring up to his classmates; and first graders realize this. Making matters worse, many ADHD students are made to feel unsuccessful with both direct and indirect responses that they get from teachers, even well-meaning.

Early Identification

I work as a school-based occupational therapist and maintain a private practice, and in these environments, we can often pinpoint very young children who are later going to be diagnosed with ADHD. These kids may have been expelled from school or sent home from playdates at a young age. However, mild cases of ADHD are often missed for years, especially in girls or in children who have the inattentive type. The student, parents, and teachers sense that something is wrong, and that the child is struggling but they just can’t put their finger on the underlying cause.

It is so important for educators and parents to realize that these difficulties are due to ADHD as early as possible. The later the diagnosis of ADHD, the more likely secondary symptoms are to develop. The early years of school are also such a crucial, formative time for children. It is during these years that major neuro-developmental processes take place. It is helpful to have an intentional and targeted method to detect the possibility of ADHD in students so that early identification can take place. Looking out for the famous primary symptoms which are the actual symptoms of the disorder will be helpful, even if they present mildly. These primary symptoms of ADHD are distractibility, restlessness, inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and executive functioning problems.

Negative Self-Image

The development of a negative self-image is quite common in kids with ADHD. The repeated failures they experience and the negative feedback they get from teachers and other adults are causes. The things people tell them make them feel that they are dumb, lazy, stubborn, willful, obnoxious, or daydreamers. These kids are often the first to be blamed when something goes wrong, even if they didn’t do it. Statistics show that people with ADHD often get in trouble, and it seems that this negativity often “plays out” in their lives. These voices constantly pull them down. Even when teachers are sensitive and respectful to the students with ADHD, the very fact that these students need to be redirected more than their peers is not lost on the students, and this further contributes to negative self-image.

Negative self-image is just one of the secondary symptoms of ADHD that can be prevented with early identification. Secondary symptoms also include depression, boredom, frustration from school, fear of learning new things, impaired peer relations, drug and alcohol abuse, and stealing. It’s important to point out that negative self-image and these other secondary symptoms are not part of the neurological component of ADHD yet are very common secondary outcomes. It does not have to be this way.

Strengths-based Model

According to Dr. Ned Hallowell, author of many books about ADHD, the primary and most effective means of preventing these secondary effects is early identification and intervention using a strengths-based approach. ADHD often comes along with “mirror traits.” Distractibility, impulsivity, and hyperactivity have positive traits that accompany them; you can think of them as the other side of the coin. A person with ADHD may be distractible but the mirror trait is curiosity. This trait leads a person to want to learn about all sorts of things. Impulsivity is a negative trait – acting without thinking – but one of the reasons why creative people are successful is that they don’t decide when they are going to have a creative thought; it comes randomly, and they act upon it immediately. Hyperactive people may not stop moving about but these are the people who have the energy to accomplish so much in their lives.

The negative traits are the ones that cause trouble for people with ADHD, and they’re the ones that attract our attention. We focus on them – why won’t this kid sit still? or why can’t she think before she talks? Of course, when we ask these questions, we create the negative self-image that ADHD kids often have. But if we flip them to notice the mirror traits or strengths that accompany them, we can start thinking of the specific strengths that our students have. We can also start pointing out these strengths to them and help them to notice their capabilities and qualities.

If we look at some additional qualities for kids with ADHD and we examine them through the lens of mirror traits we can learn how to help our students tap into their own strengths. If you have a student who seems intrusive, the flipside may be that they are eager. If a child cannot stay on point, they usually have the ability to make connections in ways others cannot see and find meaning more readily. Your student may tend to be forgetful, but they also get involved in what they are doing in a very focused manner. Disorganized kids can be very spontaneous. Stubborn children can be persistent and will not give up on something that they want to achieve. The moody child can also be very sensitive to others.

Revealing a student’s strengths has a powerful effect on how you view them in your classroom and how they view themselves and helps the student to learn ways in which to accomplish school-based tasks. The idea is for them to become aware of what is hard for them and have them harness their strengths to compensate for those weaknesses. If your student is highly disorganized and cannot ever remember to bring her materials to class or complete assignments, you would want to help her discover a strength that she can harness to compensate for her lack of organization. Maybe she is socially strong and has friends who can help her with reminders. Maybe she is artistic and can draw a diagram of what she needs for class or her locker and use that to remind her of what she needs. Maybe she is great with technology and would do well with reminders and calendars available on the school-based technology provided.

Taking a Strengths Inventory

The first step in the journey is to notice the child with ADHD and identify his or her strengths and the mirror traits that he or she possesses. This can be done through observation or by having a parent or child complete a strengths- or learning styles inventory. There are many strengths inventories available. One example is the Kolbe Index, which helps to identify a person’s mode of operating and provides diagrams and suggestions to help support the areas of deficit. There are also strengths inventories available for free online. Jennifer Fox, author of a book called Your Child’s Strengths, has a comprehensive strengths inventory and curriculum called the Affinities Program. She developed this program for high school students, but the ideas and lessons can be adapted for any grade level.

A similar idea is to use a learning styles inventory, which can be found for free online. It helps students to identify the way in which they learn best and then the teacher can use that to guide the way in which the student completes assignments and takes tests and can guide the teacher in structuring the classroom and the lessons. It can also help teachers to understand why students engage in behaviors that often annoy them and make it seem that the student is not paying attention. For example: A teacher is frustrated that a student doodles during the lesson instead of looking at the teacher or the text that is being presented. What the teacher may not have realized is that the student is a kinesthetic learner and in order to focus on what is being taught, he needs to move or focus his eyes on something that will help him to attend to what is being taught. Once discovered, the teacher can plan movement activities into the lesson (or even just for that student,) capitalizing on his learning style instead of battling him over it.

The Cycle of Excellence

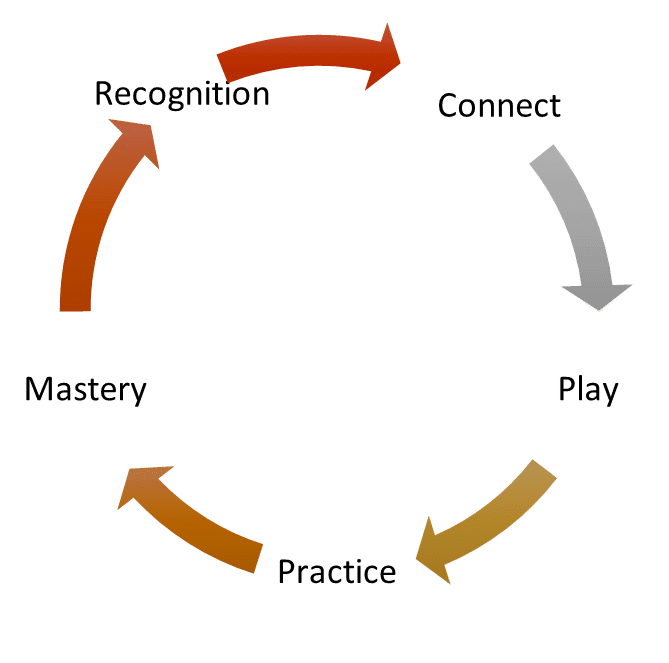

The cycle of excellence is a great practical way in which to put this into practice. Dr. Hallowell describes this cycle in detail in his book, Super-Parenting for ADD. The cycle goes sequentially, as follows: connecting, play, practice, mastery, and recognition, and then circles back to connecting (see Figure 1). Connecting means creating a connected environment for your child. Create a relationship with the child, develop a rapport, and show them that you appreciate and respect them. You do this by creating experiences together with them. This all needs to take place before you make demands and have expectations of them.

The next step is called “Play.” This refers to engaging with an activity. It can be a game, but it can also be an academic or social based task. The idea is that the child has a safe and connected basis in which to dabble and experiment and take chances; in other words, play with the activity. The child can tap into some of the strengths to help him compensate for his lag in that area. Once the child has engaged in the activity and has experienced some success, that leads to practice, which is completing the activity multiple times. This emerges naturally from enthusiastic play.

Now that the child is engaged and practicing, he is getting better at the activity that is challenging and important for his learning and development, headed towards mastery. Mastery does not mean that the child is the best at the activity, just that he is making continuous progress in this area. This stage is a huge self-esteem builder. The best way to motivate a child is to set them up to achieve mastery or make progress. But it’s important to be careful during this stage because there is nothing that can be more demoralizing than trying and failing. It is of high importance to make sure that the task is achievable for the student.

Once a child achieves mastery, they naturally receive recognition. Recognition does not necessarily mean getting a prize. It means someone noticed your progress and gave you a silent nod, a pat on the back, a thumbs up, or a great job. This in turn connects the child to the person and environment completing the cycle.

Helping our students and the children we are working with to recognize their strengths and to realize that ADHD is not necessarily a disability, but merely a different way of learning, is empowering. I once worked with a sixth-grade boy, utilizing the strengths-based model to target certain areas of need. I was about to start him on a protocol to strengthen cerebellar function, using a method called balance training. I had explained the purpose of the exercises and why I wanted him to complete them daily. He turned to me and said, “Wait! If I do this, will my ADHD go away? Because if it takes away my ADHD, I don’t want to do it.” I assured him that he would still have all those great benefits of ADHD, but this program may help with areas in which he struggles. It was so encouraging to know that this boy had such a positive association with his diagnosis and recognized how it served him well in many ways.

Miriam Gewirtz, MS, OTR/L is an occupational therapist at Special School District in St. Louis and maintains a private practice. She has led trainings and given courses and is passionate about finding the strengths of every student. Contact her with feedback at [email protected].