Start Here: ADHD

July 18, 2022San Diego Hebrew Day, San Diego, CA

December 27, 2022by Dr. Eli Shapiro

Technology is ubiquitous and inescapable. It presents tremendous educational and existential opportunities as well as formidable challenges in harnessing its maximum benefit and minimizing its inherent negative impact on functioning. Since 2014 I have had the opportunity to create and manage The Digital Citizenship Project, along with Temima Feldman. Over the past 9 years we have worked with nearly 300 school communities and organizations to fulfill our mission of teaching digital responsibility in the age of technology, through parent programs, faculty professional development, curriculum training and student workshops.

The Digital Citizenship Project approach has always been one that was guided by research. (Some of our early descriptive statistics can be found here.) In addition to using published data to inform our focus on how technology impacts the social, psychological, and behavioral functioning of individuals and families, we used school specific data to understand which methods of intervention would be most effective. Consistently, an educational strategy served as the strongest contributing factor to healthier technology use, both for parents and students. The key terms that guided this process were “thoughtful”, “deliberative”, ‘balanced”; and then COVID happened.

I, like many of you, could not find my copy of “The 10 things that effective educators do during a global pandemic that features quarantine, isolation, chaos, political upheaval, and the need to make decisions that no matter what you do is guaranteed to outrage half your parent body, board of directors, community, and maybe even family”. I think I forgot it on a flight in February of 2020. During this time we were in crisis mode. As I have said on numerous occasions, COVID-19 was not ideal, and the effectiveness of our response will be studied for decades. But one thing is certain: as a society we went from a semi-measured trickle approach with technology to a tsunami of device ownership, screen engagement, and increased dependence for many of our personal and professional needs. As I said, it was not ideal.

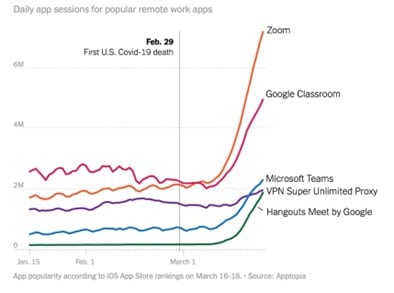

Early COVID data saw a 47% increase in broadband use according to OpenVault’s Broadband insight report of the first quarter of 2020, and while online gaming saw a 75% increase it was educational app downloads between March 2nd – 16th 2020 that saw a whopping 1,087% increase according to statista.com. (Figure 1)

With mandatory school closures and on-again, off-again quarantine guidelines, distance learning became the norm for most Jewish day Schools and yeshivot, resulting in similar increases in the use of internet-based technologies for educational purposes. Schools that had invested in devices and educational platforms prior to COVID had an easier time transitioning to a digital platform. Rabbi Eliezer Lehrer, Headmaster at Ora Academy in Rochester, felt uniquely prepared for distance learning, having already engaged the services of Consortium of Jewish Day Schools and Rabbi Baruch Noy. Rabbi Noy walked the Ora Academy team through a strategic process that included evaluation of the school community needs, assistance in identifying and purchasing the appropriate technology hardware and software, as well as training for the faculty in using the technology as a teaching tool. According to Lehrer, “when it was time to shut down during COVID we were able to shift online without any significant challenges”.

However, many schools that may have been apprehensive about the use of Internet-based technology as part of their educational strategy suddenly found themselves in crisis mode and seeking solutions. kPhone, a leader in smartphone solutions for school communities, shifted their focus from personal devices to educational devices and between March 2020 and May 2020 provided more than 15,000 Zoom-capable tablets and 5,000 Chromebooks to over 80 schools across North America. While kPhone provided the devices for access to distance learning, within days of the first schools in the Northeast closing, Consortium of Jewish Day Schools hosted series of webinars focusing on the skills of teaching remotely as well as how to manage the environment to maximize the learning taking place. These webinars were followed by nearly 30 school-based consultations conducted by Rabbi Noy.

Content was quickly being developed and within days of schools going virtual COJDS was already engaged in the process of setting up digital access for all the L’havin Ul’haskil workbooks, which has resulted in the current L’havin Connect platform. Content providers, including Torah Umesorah’s Chinuch.org platform, saw a massive increase in demand and morahchaya.com, a resource for early childhood educational videos, had more than 100,000 video views in only a few months.

Whether COVID opened a Pandora’s box of technology dependence, or it simply fast tracked the inevitable, federal and state government are invested in technology as a key a component in education and Jewish day schools are benefitting from the availability of those funds. As an example, kPhone has received requests for more than 24,000 devices through the Federal Emergency Connectivity fund (ECF) announced in September 2022, and millions of dollars are being utilized by Jewish day schools for educational technology services through Emergency Assistance for Non-Public School (EANS).

While the marketplace met the demand during those challenging days, and while excessive technology use during COVID was in many ways necessary, for many, technology use and screen engagement was excessive and unregulated. The increased focus on technology use both educationally and recreationally has resulted in a renewed interest by school leaders and parents in addressing the question whether we can once again be “thoughtful”, “deliberative” and balanced in a post COVID world.

Survey of Schools

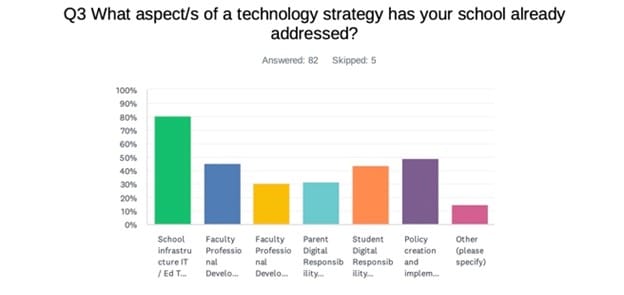

With the sudden increases in school and home-based technology use and in reflecting how schools could best approach “digital responsibility in the age of technology” we recognized that a comprehensive technology strategy that extended beyond the scope of education would be necessary. Our first step was to survey schools on their overall satisfaction with their technology strategy. In February 2022, 84 Jewish Day Schools and Yeshivot from across North America responded to our online survey and rated on a scale of 1 – 10 their level of satisfaction with their technology strategy as a 5.8. (Figure 2)

While a comprehensive technology strategy addresses multiple categorical touchpoints, we have found that school communities will often address technology in a piecemeal fashion usually prioritizing and responding to the most pressing need. The most commonly addressed technology categories include:

- School infrastructure IT / Ed Tech software / Hardware

- Faculty Professional Development – IT / Ed Tech Training

- Faculty Professional Development – Digital Responsibility Training

- Parent Digital Responsibility Education

- Student Digital Responsibility Education

- Policy creation and implementation

While the most frequently addressed touchpoint in the technology space was “school infrastructure IT/ Ed Tech”, survey responders varied greatly in the number of categories they addressed as part of their strategy. (Figure 3) Respondents also provided comments that included:

“We don’t have anything in place yet.”

“We have done all the training and infrastructure, but that was already a number of years ago. We need to update all the systems and continue training.”

“Some of all of the above.”

Further analysis of the data found that schools that addressed between 1-3 of the categories above had a lower overall satisfaction rating of their technology strategy (3.17) compared to schools that addressed between 4-6 categories (6.63), suggesting that when more aspects of technology get addressed as part of strategic plan, it will yield better outcomes and higher levels of satisfaction. This understanding of the positive impact of addressing and aligning multiple categories in the technology space should inform the overall strategy for schools moving forward. In the age of technology, it is simply not enough to provide school managed Chromebooks and laptops without a well-developed acceptable use policy (AUP), educating the school community on digital responsibility, training faculty in digital pedagogy and creating a culture of expectation and communication.

In a recent JEDIT workshop on acceptable use policies for school devices, Avi Bloom, Director of Technology at SAR High School in Riverdale NY, identified the importance of a well-developed AUP and the mistake that many schools make by starting with an AUP. “An AUP a critical step in a process that has to draw on the values and philosophy of the school”, but before policy there needs to be clearly articulated values to guide the creation of that policy.

Organizations and Resources

While the work of The Digital Citizenship Project has been and continues to be educational in nature and addresses 2 of the 6 above mentioned categories, the realities of what a school communities need to address technology effectively and efficiently in a comprehensive and strategic manner requires a wider range of knowledge and expertise.

Fortunately, there are individuals and organizations who have had demonstrable success in addressing these categories and are currently collaborating to streamline the process for schools under the banner of KETER (Kehila Technology Education and Resources). KETER continues to explore emerging resources that benefit school communities and work with leading organizations like TAG (Technology Awareness Group) for filtering, Project Trust for individual guidance and support, and Safe Telecom, a kPhone alternative for android users. But most importantly KETER serves a single point of contact to help school communities identify and espouse their values around technology, assess their needs and develop a comprehensive strategy to meet them.

kPhone serves as the leader in the personal device technology space, helping school communities manage devices consistent with their standards, values and overall health and well-being. kPhone works with school leadership to provide premium filtering, support, and a user experience to maximize the satisfaction of all school community stakeholders.

Through a host of customized services, JEDIT (Jewish Ed Tech and IT), a division of the Consortium of Jewish Day Schools, supports Jewish day schools by providing consulting, targeted professional development, and recommendations based on each school’s unique culture, current infrastructure and ability and desire to expand their informational and educational technologies. Under the leadership of Rabbi Baruch Noy, JEDIT is elevating the conversation around the hardware and software that helps a school operate and maximizes the opportunities for successful outcomes in the educational technology realm.

M.U.S.T. (Mothers Unite to Stall Technology) is dedicated to helping parents build consensus on delaying personal device ownership and social media engagement. Research suggests that it is the communal norms and peer pressure that drive the onset of personal device ownership and social media membership. M.U.S.T. is a must for elementary age school communities that are seeking to influence the social norms to where personal technology is not a driving factor in community culture.

Project Focus is a Chicago based movement dedicated to creating community-wide awareness of the many ways technology impacts our lives and relationships. Having successfully organized gatherings in Chicago, Cleveland, and Los Angeles, Project Focus continues to develop valuable educational resources that help motivate communities to promote healthy technology use and effect a culture of change in our relationship with technology.

What is clear is that the opportunities and challenges of technology, both at home and at school, are continuously evolving and school communities must continue to adapt and adjust. While school leaders are accustomed to identifying and addressing educational priorities, unlike core subjects, curricular matters, pedagogy, and leadership, many find themselves in the unique position of establishing norms, policy, and educational strategies in an area where they have far less expertise and confidence. However, the key is developing and implementing an effective technology strategy and building a support team within your school community. Mrs. Ahuvah Heyman, Director of B’nos Yisroel in Baltimore, was not a technology expert when the need to develop a comprehensive technology strategy emerged in her school community, but she knew where to turn within her faculty and created a technology team that meets on a weekly basis to discuss ongoing and emerging technology challenges. According to Heyman, “the weekly meeting puts us all on the same page and as the school director it keeps me informed of everything I need to know about technology in our school and allows me to prioritize and guide a process that ultimately improves student education”.

Professional Learning Communities

Effective education is not a pursuit by an individual, but rather a collective effort by all within the school community. To harness the collective wisdom for better student outcomes, school leaders are increasingly turning to a process called a Professional Learning Community (PLC). A PLC is defined as “an ongoing process in which educators work collaboratively in recurring cycles of collective inquiry and action research to achieve better results for the students they serve” (DuFour, DuFour & Eaker, 2002). Many school leaders may be familiar with a Child Study Team. This is usually an internal team of educators consisting of school administrators, student support staff, classroom teachers providing an interdisciplinary approach to discussing the needs of individual students. A PLC differs as it expands beyond the internal educators to include other members of the school community. A technology PLC may include parents, board members, representation of the Vaad Hachinuch, an outside IT support representative, and even students. At a recent Technology PLC that I participated in where the school did not have a dedicated IT person, a high school student who was a member of the PLC pointed out it would not be ideal to purchase google Chromebooks when the school’s primary software was Microsoft based.

A PLC is the ideal mechanism for schools to develop and maintain a comprehensive technology strategy by using a process called ADEPT.

- Assess

- Design

- Educate

- Process

- Tweak

Assess:

During this process the PLC will first explore and articulate its values around technology. It may include statements like, “We believe that technology plays a fundamental role in educating students today and we are committed to providing faculty, students and parents the necessary resources to maximize what technology has to offer.” The PLC would then assess whether there is in fact consistency between the espoused and enacted values. Is the school providing the appropriate devices and software to meet their goals? Does the infrastructure support effective and efficient use of technology in the classroom? Has there been education to support responsible use of technology for both students and parents? Has the faculty been trained in the use of technology for their respective subject areas?

A different school’s value statement may look something like this. “While there are some efficiency benefits to technology, the consequences of its utilization for educational purposes far outweigh its benefits and in our school community we will avoid the use of educational technology”. In their assessment the PLC would ask questions such as what is our policy regarding homework that promotes internet use? How do we address student use of technology for recreation purposes? Is there a role for PowerPoints and videos in the classroom and what, if any, is the process for approval? Are technology restrictions to be limited to just pedagogy or other areas including communication, assessment, and finances?

At this point the goal of the PLC is to identify what they want or don’t want out of technology and assessing whether they are addressing it properly in the above-mentioned categories of

- School infrastructure IT / Ed Tech software / Hardware

- Faculty Professional Development – IT / Ed Tech Training

- Faculty Professional Development – Digital Responsibility Training

- Parent Digital Responsibility Education

- Student Digital Responsibility Education

- Policy creation and implementation

Design:

In most cases the PLC will be able to identify many areas that need to be addressed in the assessment. During the design phase the PLC will further articulate its comprehensive technology plan but will now prioritize, calendar, and assign task responsibilities. For example, if a school has determined to use Chromebooks in the classroom, the device distribution would have to take place after ensuring that the Wi-Fi is capable of handling the increased load and that the teachers have been sufficiently trained in using the devices. Failure to follow that order will result in sub-par lessons that never get past the introduction as devices fail to connect and pages load slower than a 56k modem from the 1990s.

Other aspects of the design phase include clarifying acceptable use policies, plans for parent education, digital citizenship curriculum, personal device policies, and more. For example, if the policy for a high school is that only a personal phone filtered by kPhone is allowed to brought into school, what is the process for verification? Who on the PLC is coordinating the setup and who is approving app requests and adjustments? All of this must be clarified before moving on to the next phase.

It is never a bad idea to send out surveys (digital or paper; depending on your resources and values) to collect data and take the pulse of the parent body. This will help ensure that the PLC is generally aligned with the school community and help mitigate the vocal minority of the inevitable outliers that disagree with the strategy the PLC.

Educate:

While a PLC represents the values and interests of a school, it is in this phase where the comprehensive technology strategy is brought to the rest of the school community.

During the education phase you are outlining the designed plan. Ideally the CTS will be shared with faculty followed by the parent body and can be done in writing, video messages, zoom or in person meetings. If there will be an in person or interactive zoom, a written version of the CTS should be distributed in advance and any questions or concerns should be communicated prior to the public event. If the phases of assessment and design were conducted in a thoughtful and deliberate fashion, articulation of your goals and educating the school community should have only the expected bumps in the road.

There will of course be the outliers that feel that the comprehensive technology strategy is either too liberal or too draconian, or both. Keeping those usual suspects in the loop and validating their concerns will go a long way in mitigating the potential chaos they can cause. Additionally, survey data that supports your strategy will provide resources to ensure that the interests of the silent majority are being represented.

Process (implementation):

After educating the community comes the process of implementation. It is here that the work of the PLC is actually being put into practice. In most cases there will be segments of your CTS that is already in place and may require no adjustment or only small adjustments. In some cases, aspects of your CTS will be brand new or require a significant overhaul. Implementation requires PLC members to have tasks that they are accountable for and an expectation of reporting back to the PLC on a weekly basis. Many aspects of the CTS are dependent on one another, and collaboration, communication, and systems are essential for success. When Mrs. Heyman and the Technology Team at Bnos Yisroel determined that all reimbursements request needed to be filed digitally with a picture of the receipt, they were aware that not all of their teachers had smartphones. To address this, a tablet with a camera and instructions for reimbursement submissions was installed in the office so all teachers could be in compliance. Heyman shared that “those are the kind of things that come as part of being part of a cohesive team and having a weekly opportunity to bounce ideas off of each other.”

Tweak:

No strategy is perfect, and technology is always advancing and developing. Who would have ever thought that portable storage would require more than a 1 mb compact floppy disk? Nonetheless, a CTS should be capable of evolving as a school community’s needs evolve, yet it should always be reflective of core values. Tweaking is not indicative of failure; it is a natural part of the ongoing process and brings us back to assessment.

Comprehensive Technology Strategy

In closing, technology is ubiquitous and inescapable and whether embracing or pushing back on it, today’s educational landscape requires a comprehensive strategy to address it. Increasingly school leaders are called upon to guide their school communities through a new era of educational needs and Professional Learning Communities can serve as system to drive the student educational experience and its outcomes. When it comes to technology, a PLC can be an effective approach to developing a sound Comprehensive Technology Strategy and a vehicle to become ADEPT.

Becoming ADEPT is not a simple process, but fortunately schools and their PLC’s have resources to lean on. Organizations like KETER and their affiliates, JEDIT/COJDS, The Digital Citizenship Project, kPhone, Project Focus, MUST and more are available to guide and support school communities in all aspects of their technology journey.

Dr. Eli Shapiro is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker with a Doctorate in Education. He is the Creator and Director of the Digital Citizenship Project and KETER and serves as the Director of Educational Initiatives for The Consortium of Jewish Day Schools.