How to Design Professional Development that Staff Want to Attend

August 5, 2019

Technology in Jewish Education: Values and Accessibility

June 3, 2020by MRS. MIRIAM GETTINGER

We have all been there. In the midst of a hectic day overloaded with myriad teaching and administrative responsibilities, we are compelled to watch a 90-minute webinar on some esoteric topic or new state regulation. Indiana recently adopted a new standardized state assessment of Math, English, Science and Social Studies entitled ILEARN (because everything with an I in front of it creates marketing propinquity!), and this summer I sat through such a webinar in preparation for the release of the scores. ‘Azehu chacham halomaid mikol adam.” Believe it or not, from the dry, didactic webinar I learned to distill assessments into a simple metaphoric acronym: CARS. Ever the semantic learner, I appreciate rich vocabulary-intriguing acronyms and figurative language. CARS “drives” the four steps of assessment data- collect, analyze, reflect and strategize, adjuring us to utilize this data to plan, revise and implement differentiated curriculum based upon the documented needs of our students.

(Ironically, when the state scores were published, there was a precipitous drop in the percentage of students passing these 3-8th grade exams; embarrassingly, less than a third of the students in Indiana were proficient in the measured standards. Smugly, I was relieved that our school was rated #10 in the state in English Language Arts and the highest overall in science.)

Statistics tell a significant story; numbers weave an evaluative narrative that compels us to drill down and analyze their meaning as baseline information informing growth projections and strategies for improvement. Whether they reference classroom quizzes, tests, schoolwide standardized exams or alternative assessment rubrics, assessments are ‘ILEARN’ opportunities for teachers, curriculum specialists, principals, parents, and students alike. As the Ramban depicts them, all of life’s tests and challenges are “litovat haminuseh.”

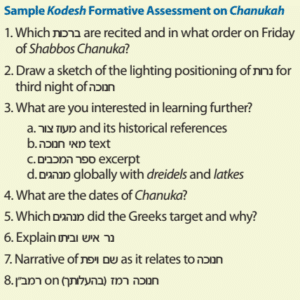

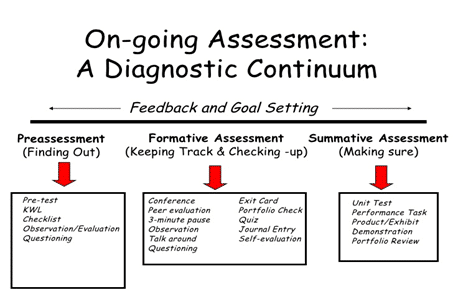

Formative Assessments

Formative assessment, both as pre-assessment as well as ongoing testing throughout the unit of study, is ironically an oft underutilized assessment tool, although it potentially yields the most pragmatism and benefit in the instruction process. Traditionally, teachers start at the beginning of the unit and march through their curricular content to the end, usually their textbook chapter or perek/inyan, with nary a clue as to what the students actually already know about that content, what they are genuinely curious about learning, or if they are in mastery of the requisite skills and conceptual understanding for successful learning until the end of the process.

As British podcaster and education laureate educator Craig Barton famously quipped that “teaching without formative assessment is like painting with your eyes closed!” Barton believes that ‘responsive teaching,’ as he terms this approach of diagnostic questioning, checks for understanding in real time and improves teaching and learning before it is too late. It’s just like what a speaker or presenter says when trying out the microphone and projector equipment prior to their stage event… testing, testing 1, 2, 3!

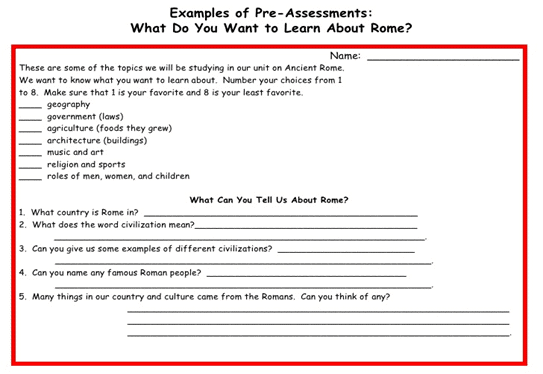

Pre-assessing in any subject or grade level facilitates differentiation and allows for ability or interest grouping – whether chavruta pairings, small groups, or larger classroom jigsaws – in mastering content knowledge or mastering textual skills. For instance, a survey questionnaire about Ancient Rome asks students to rate topics of interest to them relating to the upcoming unit of study, as well as some basic and deeper conceptual questions about the material itself, so the teacher has critical baseline knowledge of his or her audience. This prevents unnecessarily reteaching material already mastered or skipping content mistakenly presumed already known. The teacher can instead appropriately craft lessons targeting student interest and needs. Why reteach the early sections of Megillat Esther or the Haggadah year after year when students have already mastered that material and wish to learn Perakim chet-yud or Chad Gadya?

While CoJDS’s JSAT is designed as summative assessment, it can readily be adapted to formative assessment providing a crucial baseline of information about student textual skill proficiency as well as cumulative knowledge, informing school curriculum planning and progress monitoring in comparison to similar schools or the national norms. The Tableau Reader application, used by JSAT to display results, overlays the data constructively and meaningfully for principals, teachers and parents alike in understanding where their student is in the instructional continuum.

Ongoing Assessments

Ongoing assessments are actually assessments for learning rather than of learning. These can take the form of diagnostic questions, exit/admit tickets, or sticky notes where students (in under two minutes) respond to a query asking them to paraphrase, give an example, and a non-example of a concept, cite a phrase from the text, or depict a salient point of the lesson in a sketch format, with the goal being that both the teacher and the student can identify where they are in the learning process before homework or a summative test. In math instruction, formative assessment may present as a diagnostic question posed to the class which tests a single skill or concept through a multiple choice question which is unambiguous and which, significantly, cannot be answered correctly while holding a key misconception; reviewing student responses on individual whiteboards or finger designations expediently indicates mastery or the precise area students are struggling since one answer is correct and the other three reveal a specific mistake needing reteaching.

Each diagnostic question takes no more than two minutes and an ideal lesson may contain at least two such documentations of learning. Playing on exit ticket strategies, they are ungraded and can even be written anonymously (the teacher will soon recognize handwritings, but the students feel so much more comfortable to err!)

Answers can be placed on a stoplight design, with green for students who feel confident with their responses, yellow for those with additional questions, and red for those who are confused – as long as they assign words to their lack of understanding. Psychologist Allen Mendler’s quip to the typical “I don’t know” response: “Well, if you did know, what would you say?” helps cue the student to identify exactly where he or she is lost or confused in the lesson. I even suggest calling up one student daily to the desk while others record their exit ticket responses to have them unpack their thinking orally for you. While these activities require planning and deliberation, they provide a treasure trove of data in the instructional process.

Summative assessment results should not be a surprise for either the teacher or student with properly planned formative assessments throughout the instructional process. These tests should align to the instruction in both content and presentation mode. Interestingly, if you taught through lecture or auditory discussion format and then expect students to take a written visual test, the mismatch of visual and auditory memory cues comes in to play. By way of example, on a Chumash test with “mi amar el mi” questions, the teacher should read the questions aloud to the students as the mere sound of the teacher’s voice matching their instruction of the pesukim will facilitate memory of the content!

Testing for Knowing, Understanding, and Doing

Moreover, these tests should balance mastery of content with skills proficiency, as well as critical and creative thinking skills, in the KUD model of instruction– knowing, understanding and doing. Memorization of facts and figures should be minimized, encouraging students to utilize the text for evidence documentation, and in the case of kodesh subjects, for familiarity and comfort with these resources as they advance to lifelong learning. In our driving CARS analogy, what is more significant- knowing and acing the rules of the road test or actually operating the vehicle in traffic? At the end of the day, we can only teach students if we reach students; forging interpersonal bonds and helping them grow cognitively and spiritually occurs through depth and relevant discussion and essay expression, measuring their intrapersonal takeaways from the content.

I vividly recall my first genuine experience with critical thinking on an exam. It was in the BJJ seminary, where Rebbetzin David’s historia tests asked us to read a newspaper article we had not seen before and analyze its significance to the content at hand. Today students are expected to synthesize information and perspectives from multiple sources critically on essay exams beginning in the intermediate grades. ’Unseen’ tests in Chumash reference the Israeli mastery determination based upon presenting a brand new wholly unfamiliar pasuk to students to read and translate with specified meforshim. And while multiple select options are often mocked as “mivchan Americayei,” carefully crafted matching, sequencing, and modulation questions asking for the best example or the least likely to result from, etc., demand inherent critical thinking, and, of course, are expedient to grade! Creativity and creative thinking can be part of our assessments; students interpret data, draw and explain a cartoon, or connect a visual to the unit of study.

Technology vs. Paper/Pencil Exams

In today’s technological world, we ought to reflect upon the role of digital testing, both formative and summative, in impacting student proficiency and as evidence of their learning. Interestingly, research has shown that without “spatial thereness,” students of all ages are less likely to scroll up and down in rereading content information or searching for passages in the text, nor are they likely to utilize the digital tools afforded them (highlighters, rulers etc.) while testing online. Just the physical tactile step of holding and recording answers on paper vs. technology devices slows the students down and affords critical “friction” in their thinking, so they are not instantly pushing buttons and keys and randomly guessing at questions.

In fact, on the NWEA- Northwest Education Assessment, a premier general studies formative assessment taken on computers, a sloth image appears on teacher’s screens when the computer senses random guessing and rushed responses on the part of students! Additionally, rereading and searching text is more cumbersome on a screen, to say nothing of the more challenging editing skills required in longer written responses. In the digital age of “instanticty,” students are not primed to deeper and more deliberate thinking and reflection. In fact, the state of Indiana used the variable of all schools completing the proficiency test online as a contributing factor in the significant drop of scores from last year to the current year. That said, the expediency factor as well as the cost savings on shipping and manual scoring make such testing the new reality for our students. Formative assessment opportunities with Kahoot, Quizlet, etc., will help prepare students for the alacrity challenge as well as familiarize them with the digital platform to level the playing field. Digital kiosk-style centers of education are no longer science fiction but are a modern day אותיות פורחות באיור!

Mrs. Miriam Gettinger has been a principal for the past 30 years, currently at the Hasten Hebrew Academy of Indianapolis and previously at the South Bend Hebrew Day School as well as at the helm of Bais Yaakov High School of Indiana. A graduate of Beth Jacob Teachers Institute of Jerusalem as well as Touro College, she has taught Limudei Kodesh to all ages from elementary to adult for over 40 years. Contact Mrs. Gettinger at mgettinger@hhai.org.